As the first course of soup was being served, Morales—an Aymara himself—loudly said, half in jest, “Shouldn’t we say a prayer? Aren’t there any Christians in this group?”

A few people tittered, but a mayor pointed directly at Eusebio and said, “There’s your man!”

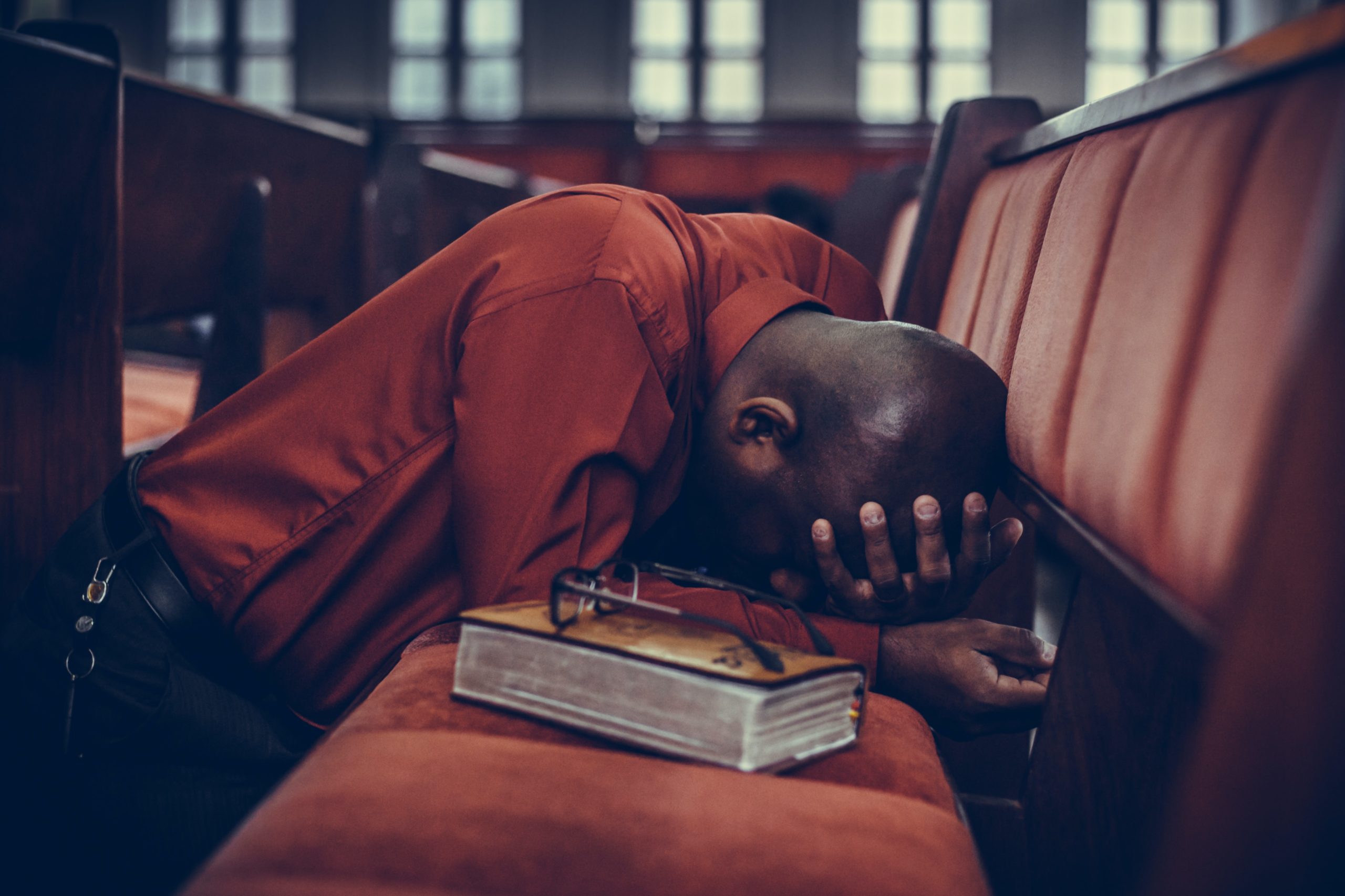

Now Eusebio felt panic. Even so, he knew what to do. He stood up…

The Aymara have been a significant presence in Bolivia and neighboring Peru for more than a millennium. Today about 2.5 million are spread across the rugged Altiplano, roughly 12,000 feet above sea level.

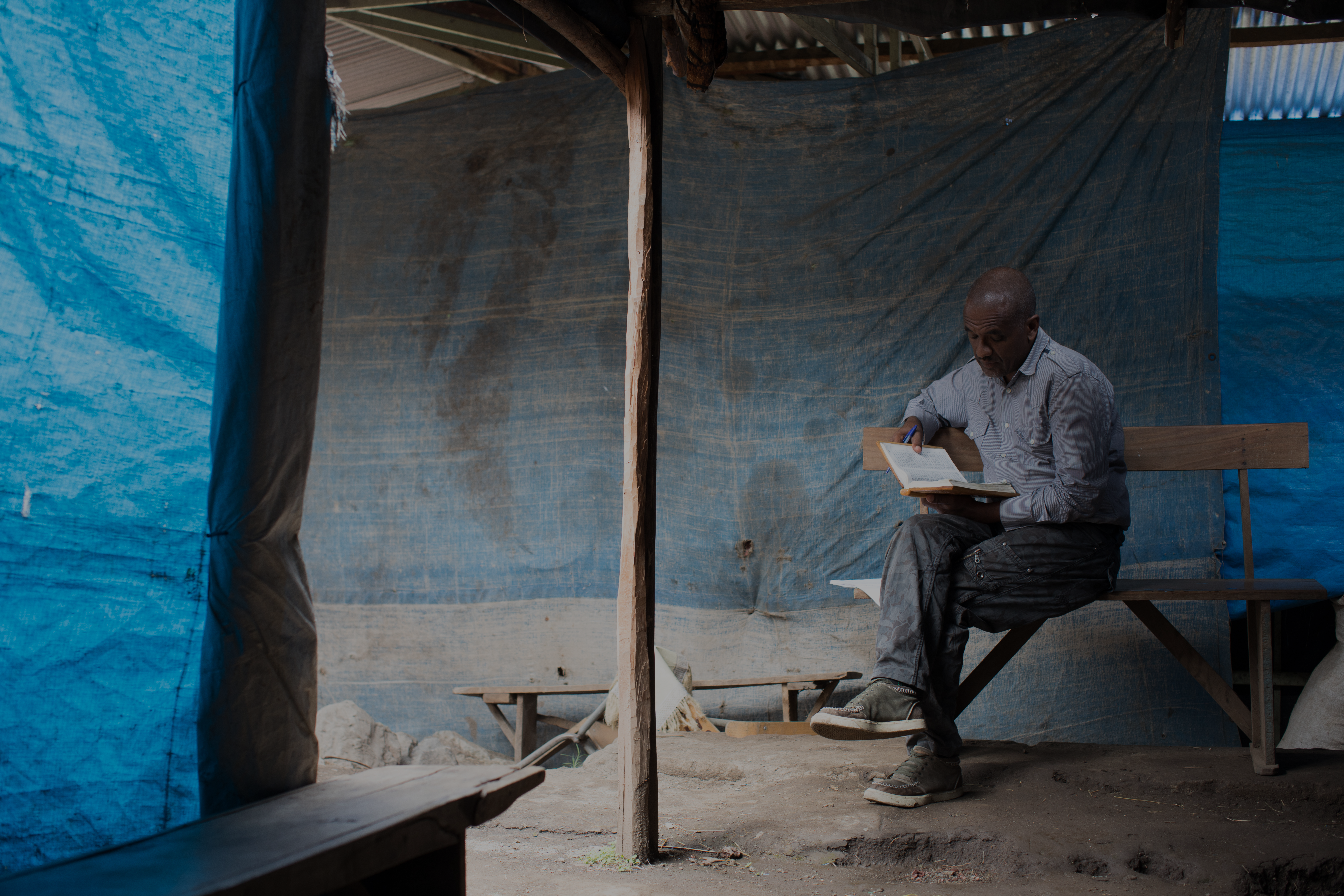

After the arrival of the first Protestant long-term missionaries at the turn of the 20th century, the Aymara proved receptive to the good news. Quaker missionaries first came in the 1930s and began preaching and forming churches among the Aymara. Eusebio’s branch of the Friends Church currently contains approximately 200 Aymara congregations.

The Friends missionaries recognized decades ago that the Bolivian church was independent and no longer needed a foreign presence. So they left.

The Aymara church continues to be strong—Bolivia now has the second-highest number of Quakers in the Americas, after the United States—but certainly is not without conflicts. Some stem from the nature of being Aymara, which is widely recognized in Bolivian society as a culture of conflict. And some stem from the early impact of the missionaries.

The first American missionaries came to Bolivia out of the vibrant Methodist revival movement in the US and brought with them its doctrines and behavioral standards. Aymara culture favors formality and set rules and procedures, so it was a good fit for this imported faith from the beginning.

While most of these emphases were positive and produced the fruit of a growing church, some proved troublesome. Among these was the teaching that Christians need to separate themselves from the world—a true doctrine theologically that can become false when taken to extremes.

The Aymara are a communal culture, with the community as well as the extended family playing an important role. As each Aymara boy reaches adulthood, he steps into a network of community obligations. These year-long service opportunities come up as an Aymara man progresses through life.

The problem for Aymara Christians is that the obligations include numerous fiestas where ritual acts and drunkenness are expected. A good leader takes his turn supplying the liquor for the gathering. In addition, these times of service require participation in animistic sacrifices to the spirits believed to protect the community.

Because of these dubious aspects, early Protestant teaching demanded that Aymara Christians refuse their community service. This produced severe tension between the church and the community.

Over the years, individuals in evangelical denominations have responded to this tension in different ways. Some believers have completely refused to participate; of these, some have suffered persecution, including loss of property. Many others have announced they are retiring from the church during their years of service; they then perform all the obligations. Some of these return to church after their years concludes, publicly confess, receive forgiveness, and are reinstated into their congregation. Others never return.

And then there are those believers who take the difficult path and manage both to serve their communities and to maintain their Christian testimonies. Eusebio is one of these.

Enjoying the Globe Issue?

Order your Deluxe

Print Edition Today!

Share Article